The English language doesn't exist – it's just French that's badly pronounced

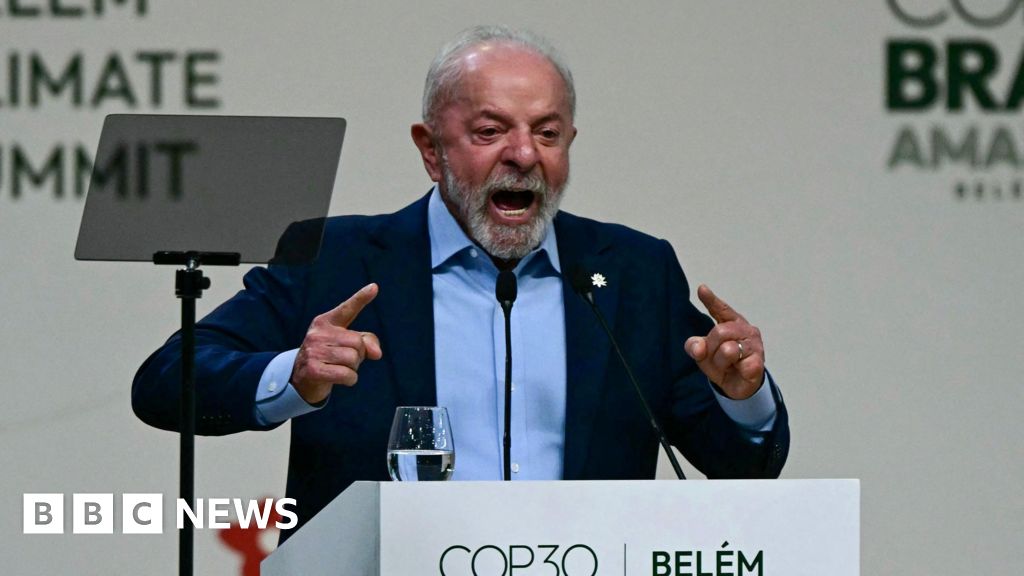

Richard Good

Is English nothing more than a regional dialect of French?

That’s the wilfully provocative claim made by linguist Bernard Cerquiglini in his new book, La langue anglaise n’existe pas, c’est du français mal prononcé.

It’s an entertaining and stimulating essay – and a highly recommended read for learners of French

Saved from being Dutch

The title of the book translates as “The English language doesn’t exist – it’s just French that’s badly pronounced” , which is a quip First World War French President Georges Clemenceau used to make. The author admits from the outset that he’s writing somewhat tongue in cheek. But he’s a distinguished linguist – and he pulls no punches as he sets out his case.

The conventional wisdom is that English is essentially a Germanic language, Anglo-Saxon, with a layer of French vocabulary added on top in the wake of the Norman Conquest.

Cerquiglini argues that the role of French in the birth of the English language was much deeper than is generally admitted. It is the French influence, he says, that saved English from being just another variant of Dutch. As such it was French that equipped English to become the language of international communication, a state of affairs which should be celebrated as la francophonie’s greatest achievement.

Ties of paternity

The core of the essay sets out the ties of paternity linking Latin, French and Norman to the English language.

Half of all English vocabulary comes from those three Romance roots, compared to less than a third that comes from Germanic sources.

Cerquiglini shows that it’s the Norman accent that explains the differences between French and English in pairs like guerre > war, jardin > garden, coussin > cushion, marché > market, bouteilleur > butler. English, he says, is not so much badly-pronounced French, but French pronounced with a Norman accent.

Why has the vibrancy of Norman culture in England been ignored for so long? Eighteen of the twenty French books that have survived from the 12th century were written in Norman dialect. Cerquiglini argues that playing down Norman influence suited both British and French scholars. The British wanted to assert their independence. The French viewed Norman as a heretical (and inferior) version of Parisian French.

Separate paths

From the 15th century onwards, English and French went on their own separate paths. As usage has evolved, words with identical origins have finished up with different meanings, creating faux amis between the two contemporary languages.

Sometimes it’s French that’s evolved. Les forains in French used to have the same meaning as the English word foreigners, whereas as today forains identifies people associated with travelling fairs.

Sometimes it’s English that’s evolved. The French adjective niais(e) describes someone who’s a simpleton. That too was the old meaning of the English word nice, which only took on positive connotations in the 18th century.

Désesperanto – the new global English

While Cerquiglini is happy to celebrate the common roots of the French and English languages, he has no time for the global airport English of international communication, for which he coins the wonderful term désesperanto.

It’s galling for him to hear words of French origin being fed back into the language with anglicised pronunciation. French business leaders now pronounce the word Challenges with an English ch sound, though the word existed in old French with a soft ch. An e-mail is un mail (pronounced in the English way), though the word’s origin is the French noun la malle meaning a leather bag. Cerquiglini prefers courriel.

He describes the input of anglicisms as a battle between regional dialects (English being a dialect of French). But he’d much rather global English were binned completely, with AI translation enabling people to speak to each other using their native languages.

Conclusion

English isn’t a dialect of French. The grammatical structure of English is almost entirely Germanic and no amount of sophistry can change that.

The author knows this of course. His point is not to win the argument, but rather to give a new perspective on the traditional rivalry between the English and French languages.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0