Under 40s Declining Memory

Cognitive Disability

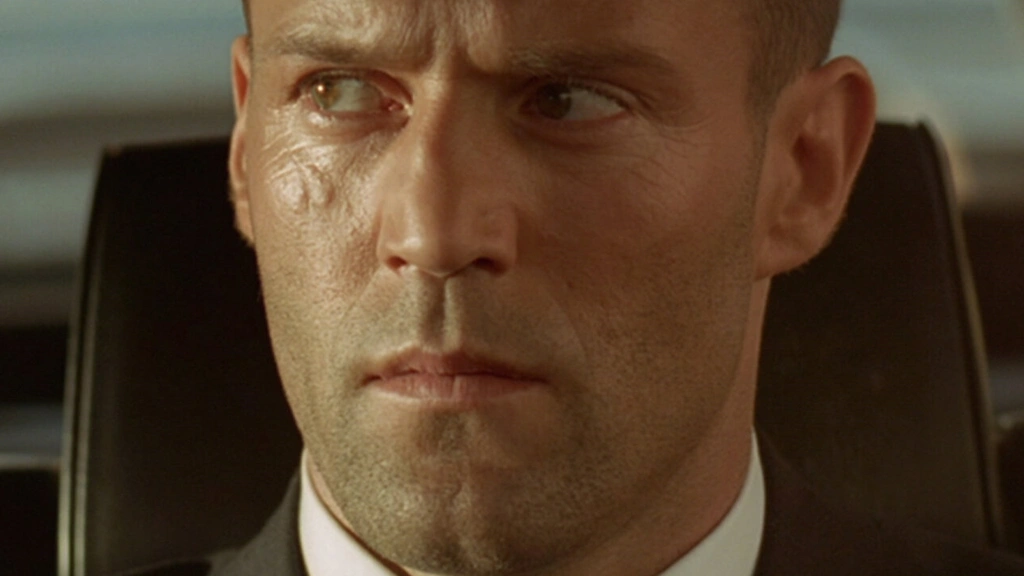

Has social media engineered the collapse of the human mind? The answer is yes, if we believe the results of a measurable scientific research of this catastrophe, which was recently published in the journal Neurology. The paper, by Ka-Ho Wong and colleagues, is a data-rich examination of 4.5 million survey responses. Its finding is that “serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions” is no longer a fringe complaint, but a surging public health crisis.

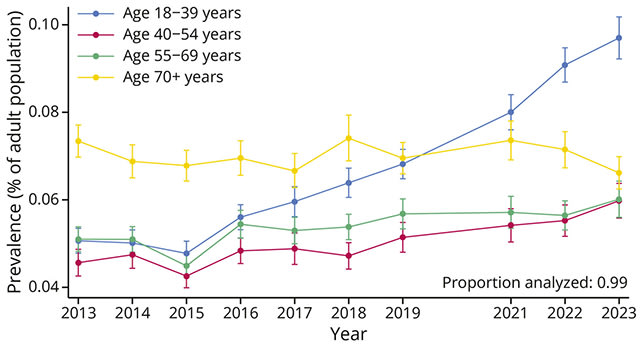

Those 4.5 million survey responses were gathered over a decade through the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Its outcome is clear on the data, more and more younger people have: serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition.

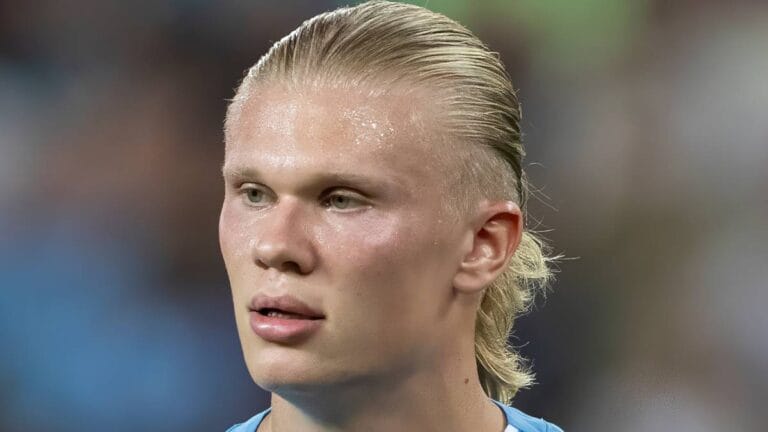

The numbers are unambiguous. From 2013 to 2023, the age-adjusted prevalence of such “cognitive disability” in U.S. adults rose from 5.3 to 7.4 percent. But the real shock lies in who changed. Among adults 18 to 39 years old, the supposed cognitive prime, the prevalence nearly doubled, from 5.1 to 9.7 percent. It climbed across every racial and economic line. It tripled even among the highest-income bracket, those meant to be buffered by privilege.

This being said the authors do acknowledge that “Younger adults, racial minorities, and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are disproportionately affected, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions.” And, with scientific rigor, the researchers “excluded participants who self-reported depression … to better identify non-psychiatric cognitive impairment.”

Because what they have found is not a disorder hidden in a subpopulation. It is the first measurable biological signature of a civilization rewiring its own nervous system.

Disattention

For fifteen years we have been building, at planetary scale, a machinery of disattention: social platforms that auction attention by the millisecond; search engines that outsource memory; feeds that weaponize emotion for engagement. The result is an economy that grows in inverse proportion to our capacity to think. Now the data have arrived like a coroner’s note. The youngest generation, those who have never known a world before the machine, are reporting that they can no longer concentrate, remember, or decide.

The authors, although cautious, propose the polite hypotheses. Social isolation. Increased reliance on technology. Maybe “greater awareness” of cognitive problems. One almost applaud the decorum and understatements. A “greater awareness” of forgetting, what a phrase. As though we are choosing to notice that our minds are leaking. People are not more willing to report it; they are less able to conceal it.

The study itself betrays the timeline. The statistically significant rise began in 2016, four years before lockdowns, before “long COVID.” The pandemic did not cause the decline; it simply sealed us inside the apparatus that was already doing the work.

And what an apparatus. We have built a trillion-dollar system to externalize thought, then act astonished when the interior world collapses. To name “reliance on technology” as a risk factor is like diagnosing “submersion” in a drowning victim.

What the paper records is not a warning but a postscript, the data catching up to what daily life has been telling us for years.

Hovering Mind

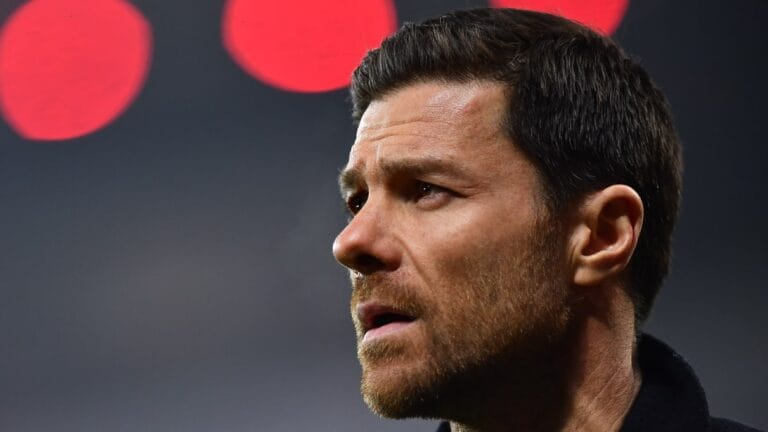

A friend of mine, a novelist, disciplined, once able to lose herself for hours in text, told me recently that she can no longer read a book. Her eyes move, but the mind skitters. “It’s as though my attention has been trained to hover,” she said, “like a cursor that can’t click.” The Wong et al. study gives her condition a bureaucratic dignity: cognitive disability. Her failure is no longer moral; it is systemic. She is not weak. She is collateral damage from being constantly online.

Yet this is larger than individual suffering. A population unable to concentrate, remember, or choose is not merely an unproductive workforce. It is an ungovernable polity. Democracy presumes a citizen capable of following an argument across paragraphs, of remembering yesterday’s promise when voting tomorrow. If cognition fragments, so does self-government. A people who cannot remember are condemned not just to repeat the past, but to be told what the past was, and to believe it.

The political question of our century is no longer who controls the means of production? but who controls the means of perception?

Perpetual Stimulation

In that light, the paper’s most haunting choice, the exclusion of the depressed, acquires philosophical weight. The researchers sought a “clean” signal, free of affect. They wished to see the thing itself. And what they found was a doubling. Perhaps this is the affect. Perhaps the mind, faced with an environment of perpetual stimulation, begins to disable itself as a last act of defense, a biological attempt to lower the volume by breaking the dial.

Meanwhile, at the far end of the data, a small mercy: among adults 70 and older, the prevalence of cognitive disability has declined. They are, in statistical terms, the last generation to have lived most of life before the feed. Their synapses were wired by books, conversations, and silence. They can still recall what it felt like to finish a thought.

The young cannot. They are digital natives in the truest, bleakest sense, born in a country that remembers nothing of itself.

Wong’s paper will be filed, cited, and forgotten like the rest. But read plainly, it documents the first epidemiological evidence of a cognitive collapse engineered by design. The authors close with professional understatement: the findings “warrant further investigation.” One hopes we remain capable of conducting it.

Stay curious

Colin

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0